।। Khandakar Elahi ।।

The World Bank and the IMF have recently published their regular forecasting reports on the performance of the world economy, which are respectively titled: “Global Economic Prospects, June 2020: Pandemic and Crisis” and “World Economic Outlook, June 2020: A Crisis Like No Other, An Uncertain Recovery.” The WB and the IMF senior economists recently presented the summary and conclusions of these reports at two webinars organised by the ‘thinknet’ Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) located in London, England.

These reports are not different from those the two supra-national organisations publish regularly. What is different about these reports is the economic context in which the recent ones have been prepared. This context is a health hazard created by COVID-19. During the past six months, all primary indicators of macroeconomic health of an economy – GDP, employment and volume of foreign trade – have been negatively affected by this virus. In other words, all these macro variables have registered negative growth, and future growths are uncertain because treatments and vaccines are not still available to contain and conquer this deadly disease.

This health-hazard phenomenon has presented a new challenge to the incumbent economic profession as it is responsible for modeling the macroeconomy of a non-socialist country. The job itself involves incorporating this health situation in our macro model so that we need not be shocked when it attacks us suddenly. Facing this challenge, in turn, entails distinguishing between COVID economics and conventional economics.

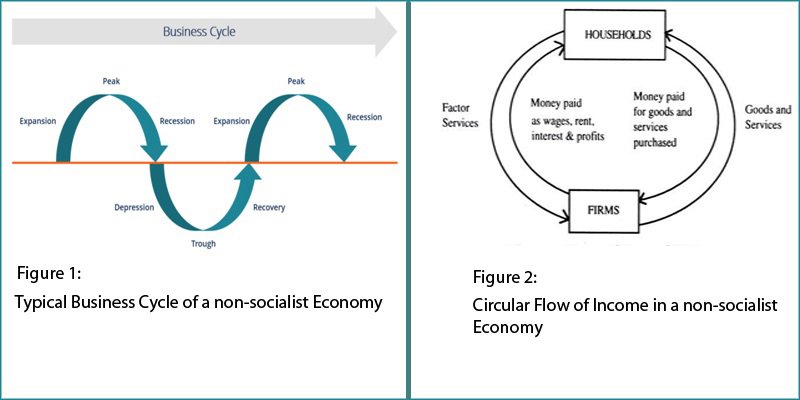

Unfortunately, the economics profession still does not see this difference, which is abundantly evidenced by the reports of two supra-national cited above. First of all, both reports describe the recent economic downturn as the beginning of ‘recession,’ which is a phase in the business cycle that is created endogenously. Figure 1 explains this idea.

In Figure 1, the red line represents the (hypothetical) steady-state growth rate of a non-socialist economy. In this economy, GDP might expand beyond its steady-state level through endogenous mechanisms due to increased aggregate demand or aggregate supply. Without government intervention, the demand-led expansion will lead to a recession to wipe out the increased demand through inflationary pressure. However, if the expansion supply-led oriented, a recession will be initiated through deflationary pressure.

This, however, is not the reason why growth has declined and is expected to decline in the world economy. Therefore, the conventional wisdom of macroeconomics does not seem very relevant for explaining this worldwide economic downturn.

Due to the COVID contagion, what has really happened, can be explained by our famous two-sector circular income flow model, as described in Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows how production and consumption are coordinated in a non-socialist economy. Households (HHs) supply all necessary factors of production – land, labour, capital and organization/management. In return, they receive rents, wages, interests and profits. Although all HH members take part in the consumption activity, the responsibility for production lies on a smaller portion of HHs, called firms. The primary job of these business ventures, viz., corporation, limited liability company, proprietorship and partnership, is to organise necessary inputs to produce goods and services demanded by the HHs. One way to distinguish between general HHs and the firms is their source of income: General HHs’ income comes from wages and salaries, while the firms’ income source is profits generated by the business. Profit is the difference between total sale revenues and total factor payments for rents, wages and salaries and interests.

If we take this model literally, then the government has no business in meddling how the two sectors interact. Its primary function is to collect tax revenues and maintain law and order situation. However, in the real world, this is not true in toto. For, the government performs several functions, including owning a part of national resources, hiring a portion of the national labour force and manipulating the behaviour of the private sector through fiscal and monetary measures. Accordingly, the effects of COVID-19 depends proportionally on the contribution of the public sector to a non-socialist economy– to be more specific, on the employment ratio between the public and the public sector.

Consider the employment structure in the US. In 2013, the public sector roughly employed 15% of the total labour force, meaning the private sector employed the staggering 85%. This employment scenario underlines the vulnerability of the US economy to the on-going COVID-19 contagion. Since 85% of employment takes place in the private sector, this sector is supposed to be responsible for the job security of its employees. In reality, the theory and policy of job security are very different. Modern economics places this responsibility squarely on the shoulder of the government, although its benefits from the expansion of wealth generated by the labour force are not very significant.

This is the point where the logic of modern macroeconomics falters fabulously. The macro model is founded on the premise that the private sector is responsible for hiring and firing (laying-off) labour as is needed to make money. In other words, it will hire when the market shows good prospects for making profits and lay off its employees when market demand dwindles. It is the government’s responsibility to take care of these laid-off employees and help them find new jobs.

The governments of the advanced democracies have been honestly performing this responsibility for many years. COVID-19 seems to have subjected this well-accepted public policy approach to severe criticism as the governments around the world are encountering severe financial difficulties in meeting its obligation. Let us look back at Figure 2 and replace the term, firms, in the production sector with the word government. This means that all HHs are now suppliers of labour and specialised skills, while the government owns all national resources and organise all production activities. This the economic model of a socialist economy, which is currently being practised in Cuba and North Korea. If this economy is locked down, say for six months, the government may not find it so much difficulty in satisfying basic needs of its citizens – food, shelter and medical care. However, the US government is unable to do so simply because the national wealth created by the 85% labour force belongs to their employers.

Governments around the world, including Bangladesh, have announced massive stimulus packages to combat the COVID-19 effects. The success of these fiscal programmes is, however, susceptible to suspicion, because COVID is an exogenous shock to the economy. Unless this health shock is endogenised in the macro model, these fiscal policy measures could trigger unwanted adverse effects on the economy: worsening government treasury position due to increased budget deficits and aggravating economic inequality. As the government pours more money in the economy for supporting the unemployed labour force, its revenue situation goes from bad to worse. On the other hand, general workers are laid-off because of the health situation, which does not affect the executives and other hierarchies in the corporation. They draw all their salaries and benefits from the corporation, although the artificial person does not make any money.

This condition can be reversed by endogenising the health shock in the macro model. For example, all employees of a corporation would accept reduced remuneration to support one aother until the work condition returns to normal. This ad hoc policy, in turn, will save the government from increasing its budget deficits for supporting the labour force. Then, the corporation needs to regularly pay installments to financial institutions for borrowing both operating and fixed capitals. The loan payments may be deferred under the government guarantee until the corporation is back to regular business.

In fine, COVID-19 may be thought of as a warning to the society of world orthodox economists that its economic philosophy and scientific model are founded on an unrealistic economic premise. If it truly believes in the virtue of capitalism and wants to help the world to retain and improve its most preferred political system, democracy, then the society of orthodox economists must review and reformulate its conventional wisdom.

The writer, Ph.D. is a former professor of economics and finance, Independent University, Bangladesh. He lives in Guelph, Ontario, Canada