Unveiling urban mobility in the struggles of Dhaka’s slums

।। Khadiza Akter Tasnim ।।

।। Md Khaled Saifullah ।।

।। Shamil M Al-Islam ।।

In the lively centre of Dhaka, where every moment pulses with energy, there’s a world that often gets forgotten — the world where urban poverty dwells. Bangladesh has a population of approximately 165.16 million with more than 1.8 million residing in slums (BBS, 2022a). Among the tall buildings and crowded streets, countless families are simply trying to make it through each day, facing struggles that go unseen by many.

In 2022, the headcount rate (HCR) using the upper poverty line stood at 18.7% nationally and 14.7% in urban areas. Conversely, the HCR utilizing the lower poverty line was 5.6% nationally and 3.8% in urban centres during the same period (BBS, 2022b). A recent study by researchers from Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB), “Measuring Multidimensional Poverty among Poor Urban Households of Dhaka City” offers a glimpse into their lives, their dreams, and their challenges.

The study delved deep into the stories of 747 households from 32 slums spread across 19 neighbourhoods of Dhaka, of which, 88.1% of respondents were residents of Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC), with the remaining 11.9% originating from Dhaka South City Corporation(DSCC). Furthermore, within the sample demographic, males represented 48.3% while females accounted for 51.70%, underscoring a balanced gender distribution in the study. What unfolded was not just data points but the experiences of those living on the margins.

Each move tells a story — of economic opportunity, of seeking better healthcare, of escaping environmental hazards, or simply of trying to find a place to call home

The study finds that families grapple with financial instability, scraping by on an average monthly income of Tk20,415. Yet, amidst all the hardship, the presence of multiple earners per household was observed in many households, striving to make ends meet against all odds. Interestingly, households consist of an average of two earning members, with a maximum of six, indicating a complex web of financial dependencies and responsibilities shared amongst the household members.

But life in Dhaka’s slums is transient, marked by constant movement and upheaval. The study explores the intricacies of household composition and residency duration in Dhaka. On average, respondents reported a residency period of 19 years within the city, ranging from less than a month to a maximum of 45 years. Notably, 51% of respondents indicated having changed residences at least once, highlighting the dynamic nature of urban living in Dhaka. Each move tells a story — of economic opportunity, of seeking better healthcare, of escaping environmental hazards, or simply of trying to find a place to call home.

Delving deeper into the data, the study unveils the frequency and reasons behind household relocations. While 41.7% of households shifted between one to five times, a smaller proportion experienced higher frequencies, with 4.7% of households shifting six to 10 times, and 2.4% of households shifting more than 10 times. Additionally, around 50% of the sample households changed houses at least once with an average of four moves per household.

These numbers show how people living in Dhaka’s slums often experience frequent changes — while some hope the change would ensure a better life but for the rest, it is just another strategy to survive in the face of uncertainty, where stability is a luxury few can afford.

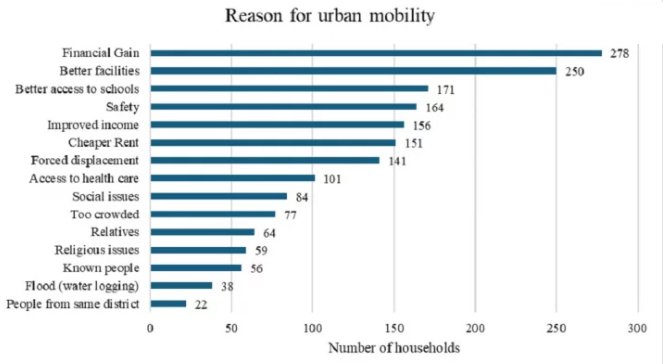

The motivations behind these relocations paint a vivid picture of the challenges faced by urban dwellers. Financial gain (37%), better facilities (33%), better access to school (23%), safety (22%), improved income (21%), cheaper rent (20%) and forced displacement (19%) are among the primary reasons cited by the households for urban mobility where multiple reasons are mentioned by some of the households. Moreover, access to healthcare, social issues, and environmental concerns, such as floods and waterlogging, crowds, and the presence of relatives, friends, and known people also play significant roles in shaping household decisions to relocate.

While these reasons can easily be overlooked as just a list of reasons behind urban mobility, for policymakers, the findings could serve as a wealth of information required to address the issue of poverty alleviation and improvement of the overall well-being of the urban poor.

Their strength and resilience show us that by crafting thoughtful, prudent policies, we can make a real difference in people’s lives, offering hope and opportunities for a brighter tomorrow. Policies should not just be about routine paperwork — it should be about connecting with our shared humanity.

In the narrow alleys of Dhaka’s slums, amidst the chaos and the noise, there are stories waiting to be heard. Stories of struggle, stories of resilience, and above all, stories of hope. For in their voices lies the key to unlocking a better tomorrow for all who call this city — home.

(Khadiza Akter Tasnim, Dr Md Khaled Saifullah, and Shamil M Al-Islam are undergraduate student, Assistant Professor, and Senior Lecturer, respectively, at the Department of Economics of Independent University, Bangladesh.)