Pradip Phanjoubam: The stories in Temsula Ao’s book are a subconscious sketch of the Naga nostalgia for a traditional world being left behind.

Book: The tombstone in my garden: Stories from Nagaland

Author: Temsula Ao

Advertisement

Publisher: Speaking Tiger

Price: Rs 499

There is something dark about this collection of five short stories by Temsula Ao. This is quite unlike the author’s earlier short-story collections, particularly These Hills Called Home, which tell how ordinary Nagas fought and came to terms with unspeakable violence in their lives. The magic moments of resistance and resilience in this struggle and the steadfast belief in the ultimate triumph of the light of goodness are distressingly absent in the present collection.

The Platform is about a Bihari porter, Nandu, at Dimapur railway station. One desolate winter, this poor but proud man finds an abandoned boy child on the platform and brings him home. Nandu decides to adopt the child after the boy’s family could not be traced.

One day, while bathing the child, he discovers that the boy is circumcised: he must, therefore, be a Muslim, probably Bangladeshi. He hides his discovery sensing trouble and the father and son live a normal life till the boy reaches adolescence. Bad company brings the reluctant boy to a brothel one day and his circumcision becomes known. The pimps and the prostitutes seem to share the bitterness that Nandu suspected, and the boy is lynched. Nandu also ends up being excommunicated by his friends and his community, forcing him to migrate elsewhere in utter defeat and misery. Can love and human bondage be so fragile?

Another story, The Saga of a Cloth, chronicling a woman’s revenge, is intense. Repasongla grew up in an Ao village. While a maiden, she was courted by two boys, Lolen and Imdong. She rejects Lolen and dates Imdong. Lolen does not take it well and rapes her. Her lover, Imdong, dies in an accident during a fishing expedition. Some suspect that Lolen caused the accident. Repasongla decides on revenge, and marries her rapist. Her moment arrives when her husband dies in one of his drunken brawls at a bar. She stealthily places the tassel of her supeti on her husband’s chest before burial. Supeti is a pre-prepared funeral cloth for every person; even touching a wife’s supeti is believed to be a great dishonour for any husband. A shared life with a brute for the sake of revenge is a strange choice. But the story does offer intimate glimpses of life in an Ao Naga village.

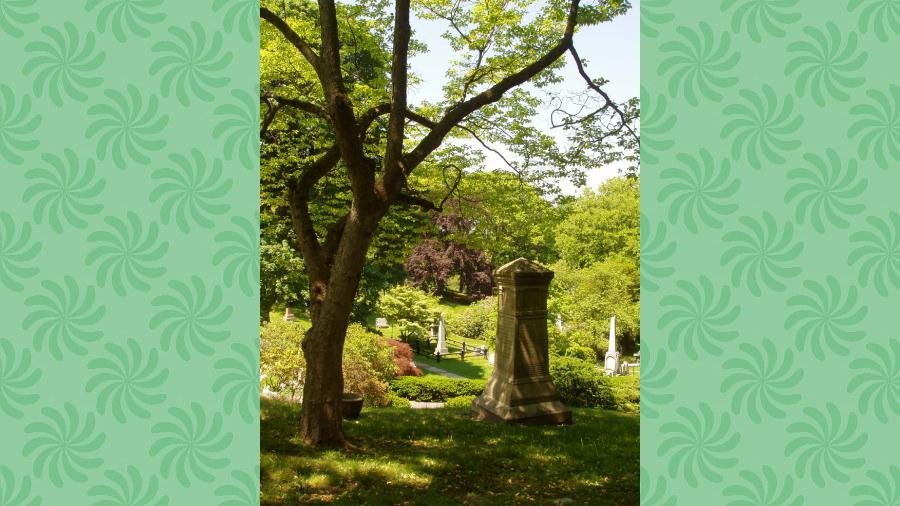

The story that shares the title of this collection is, again, about strained relationships spanning two generations. A tea planter — an Englishman — marries a dark, curly-haired plantation worker. For some reason, they resent the mixed blood of their children and, indeed, their children undergo varying degrees of social ostracism in their schools and colleges. Strangely, the father insists on an arranged marriage for his daughter, Lily Anne, the protagonist. She marries an Anglo-Indian son of another Englishman planter. Lily is never happy with her cold and brutish husband. When he dies, his tombstone in her garden becomes her albatross. Only removing and relocating it elsewhere brings her peace in her old age.

There are two other stories — Snow-Green and The Talking Tree. In these, plants are sentient beings, capable of love, anger and hate. Snow-Green is about a lily which refuses to bloom when replanted in a vase and longs for the openness of the garden while The Talking Tree is about a rebellion by plants against human loggers. In this fictional world, the familiar, oppressive atmosphere over lost freedom is evident. Perhaps these stories are a subconscious sketch of the Naga nostalgia for a traditional world being left behind.