The ‘Lost Art of Scripture’ is liminal, straddling lightly the boundary between popularization and academics

Book: The Lost Art of Scripture: Rescuing the Sacred Texts

Author: By Karen Armstrong,

Publisher: Random House

Price: Rs 799

Annie Kunnath: Karen Armstrong’s book, The Lost Art of Scripture, studies the role and the place of holy texts — at best seen as negligible, at worst a manipulative tool for justifying violence and fundamentalism — in today’s world. If, until recently, the scriptures were versatile spiritual resources, they are now atrophied and stagnant. If in the past, the scriptures helped transcend the material and the mundane and linked the human with the divine, they are currently just a set of binding injunctions with little relevance. The texts no longer woo people with their eternal truths; instead, these truths have become highly prescriptive. So if the holy texts, be they oral or written, seem incompatible with the modern world, is it because their original purpose is lost? Can the scriptures still speak to us today?

The title, The Lost Art of Scripture, intrigues the reader, while its subtitle, Rescuing the Sacred Texts, clarifies Armstrong’s intention to revisit these texts and make them relevant. This is not merely a nostalgic return to an imaginary perfection in the past. As Armstrong writes, “the sacred text was always a work in progress.” Their messages were reinterpreted, revised, engaging with the times. This kept the scriptures alive and eternal. Today we have lost the art of making the scriptures creative, appealing, and imaginative. Our slavish and obstinate attempt to return to past interpretations has stifled their voices and made them irrelevant. However, the sense of sacredness persists in the modern world despite the seeming indifference towards actively seeking the transcendent and the absence of metaphysical and ontological questioning.

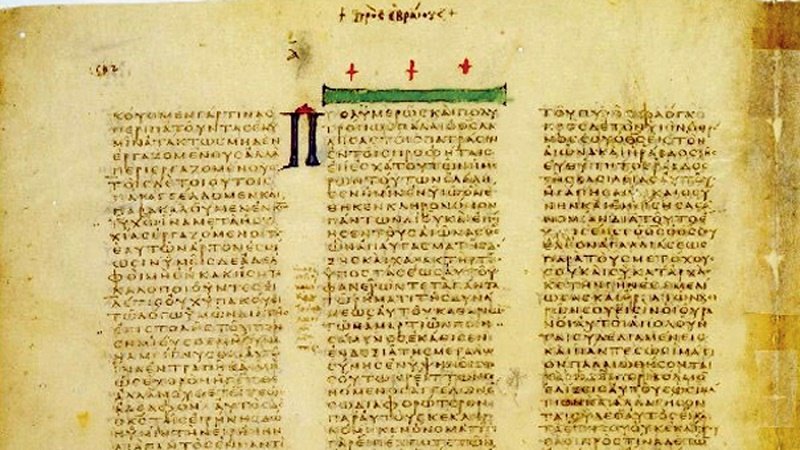

The structure and presentation of the book reflect a tripartite focus. Part One — “Cosmos and Society” — traces the chronological development process and the differences in emphasis of three major scriptural traditions: Abrahamic, Indian — especially Vedic — and Chinese. The title of this first part is particularly suggestive. It evokes the essence of these three traditions, which is either the universal (cosmos) or the particular (society). Thus, while the sacred texts of Vedic India and China emphasize order in the universe, the Abrahamic scriptures prioritize justice and equity. The word, ‘cosmos’, is to be understood in two ways. First, in its classical Greek sense, with its idea of order and adornment. The second is with reference to the meaning given to it in Hebrew scriptures, as ‘heaven and earth’, where cosmos is understood in relation to god, its creator.

Parts Two and Three — “Mythos” and “Logos”, respectively — deal with two kinds of insight, the imaginative and the analytic, and their role in understanding scripture. Modern neurology speaks of the right and left hemispheres of the brain, and their corresponding cognitive processes, while modern psychology stresses the limitations of objective and empirical knowledge.

Mythos studies myths; rituals; scripture as performative art; reading versus rhythmic chanting; public and private reading of scriptures; the place of memory and recitation in the transmission of holy texts; the power of listening to scriptures with the inner ear; the role of divine inspiration; and the intuitive imaginative mode of perception. Contrary to common understanding, myths are not tall tales. Instead, myths belong to different dimensions: historical, psychological, philosophical, moral, social, esoteric. And, therefore, they are timeless sources of inspiration, sharing “timeless truths in timeless context”. They have the power to contemplate life’s big questions without letting them douse the spirit. Myths belong to the right hemisphere of the brain, the seat of human relationships, of care, pathos, and the sense of justice and equity.

Logos reflects on the ubiquity of ‘reason’ (logos) in every aspect of modern society, be it in the reading of scriptures or in education. Today’s trend is to look at scriptural narratives through analytical reasoning while, in fact, these narratives are not factual descriptions of events or exact historical records of patriarchs, matriarchs, prophets or wise men. The art of scriptural interpretation uses specific tools and methods that demand a “disciplined cultivation of an appropriate mode of consciousness”. This implies that rationality is only a partial mode of understanding the message of scriptures. There is the less-spoken or the occulted type of consciousness: the intuitive, imaginative, leap-of-faith knowing.

Backed by important insights from psychologists and neurophysicists, Armstrong advocates the integration of the left and the right hemispheres of the brain. She justly points out that even modern education has tilted heavily towards the side of empirical sciences: towards rationality, logic, analysis. This means that the left hemisphere of the brain, the more competitive and rational side, has been privileged to the detriment of overall development and well-being. The right hemisphere, which is more altruistic, creative, has been neglected. However, from the beginning, scripture was ‘spoken’, ‘heard’, in the context of rituals, enabling participants to embody it. The chanting, the melodious recitation, the rhythmic swaying of bodies, music — everything quietened the analytical side of the brain. In the resulting stillness one ‘saw’ with awe the underlying mysterious unity of all creation.

The book ends with “Post-Scripture”. The quick appraisal of the three scriptural traditions traversed through the eyes of intuition and reason attests to the commonality of all scriptural traditions. If these sacred texts diverge on the manner of living in harmony with the transcendent, they converge on the same ethical injunction: to live in harmony, one must transcend selfishness, egotism. It is in this self-emptying (Greek kenosis), in divesting oneself of something, to live with and for others, that one becomes larger. But this requires tremendous moral striving (Sanskrit sramah). This realization that there is a commonality that binds all religious traditions is not particular to this book of Armstrong. It is the Ariadne’s thread that runs through all her works.

The Lost Art of Scripture is liminal, straddling lightly the boundary between popularization and academics. It imparts scholarly knowledge to an audience that may include non-experts, those curious and willing to get intellectually involved in the field of Religious studies or Comparative religions. If the author stresses the need for revisiting scriptures to make them relevant, she also follows her own prescription by discarding untenable views and updating knowledge. One such example is the etymology of the word, Upanishad, with its traditionally attributed understanding of ‘to sit near to’. The new meaning has taken the earliest connotation of the term as ‘correspondence’, ‘resemblance’, or ‘equivalence’.

This is an exhaustive and challenging book. And, therefore, the reader would overlook the lapses in the writing of this renowned historian of religion and its leading commentator. Like the vagueness around the term, ‘modern period’, used often but not defined; or the intermittent usage of certain terms; or the homiletic tone in some places; or the many repetitive commentaries; or that some scriptures are studied in depth, but not others, such as those of Sikhism.

Scriptures are fluid. Scriptures reflect us. All scriptures have violent and militant passages. We must take ownership of our texts and remember that religion is a matter of imagination, an art that must engage with the times. In the ongoing pandemic, this book delivers a relevant message. Yes, we must ‘rescue the sacred texts’ from the excess of logical and rational interpretations. We must re-explore our scriptures and rediscover the lost art of engaging with them in relevant, compassionate and creative ways. And in this process of rediscovery, the texts will be rescued. Intolerance and violence will be curtailed. We must rescue the sacred texts and allow them to speak to us because they affirm humanity’s potential for goodness. It is our moral responsibility — our dharma.

And perhaps we need to remember the words of the Little Prince while reading anew the scriptures: “Now here is my secret. It is very simple. It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”