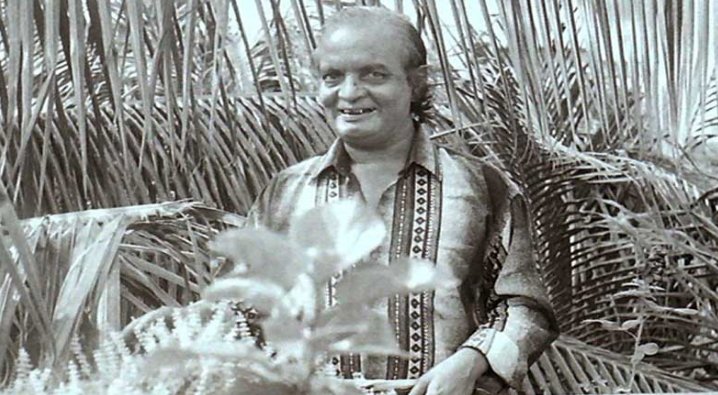

Ahmed Sofa birthday is 30 June 1943. What surprises us the most is his spontaneity in writing even though he deals with sophisticated and sensitive matters relating to religion, politics, and the formation of a nation and nationhood.

।। Ariful Islam Laskar।।

It is too difficult to evaluate the writings of a person of such a vast caliber in a short piece of write-up. Readers must encounter the original writings of the writer to taste and understand his thoughts and philosophies. Any shortcut cannot be an alternative. However, this article is nothing but a tribute and birthday (30 June 1943) offering to an outspoken novelist, essayist, poet, and translator Ahmed Sofa who did not compromise with the oppressive and evil forces of our society. His groundbreaking original essays energize me to realize and think differently, and his novels help me see our society, culture, and politics from many diverse angles and perspectives.

What surprises me the most is his spontaneity in writing even though he deals with sophisticated and sensitive matters relating to religion, politics, and the formation of a nation and nationhood. His dictions are lucid, sentences are relatively short, and every paragraph gives fresh ideas and sensation. It seems like me that Sofa is reading me a story in an easy and capitative mood. His writings are easily accessible, yet all his sentences induce the readers to stop and contemplate.

The first novel that caught my imagination and changed my view about writing a novel is Sofa’s Omkar (the Om, 1975). Here I find an original writer who is articulating every word eloquently and sentence effortlessly. Ironically, the protagonist—the dumb wife of the narrator— takes much effort to utter a single word. Dauntless Sofa, at the fag end of the novel, illustrates that the more the language movement march approaches towards the dumb wife—who then tries so hard to speak out—the more blood comes out from her mouth. The narrator-cum-husband questions ‘whose blood is redder, is it the blood of shahid (martyr) Asad or his dumb wife?’. Though tragic in mood, I just wonder in amazement: what a lucid metaphorical and rhetorical expression! The very shrewd metaphorical expression on the importance and spirit of the language movement of 1952 that I find in this novel spellbound me.

Then I read Surjo Tumi Sathi (Sun, You are My Companion). Sofa, being a Muslim, believed in religion but did have a secular outlook all through his life. This book which Sofa considers his best one reveals the life of the easy-going oppressed village people who are the constant prey of natural calamity and village matubbar. They are sometimes divided by religion. However, as a reader, I am so impressed by the way Sofa portrays the dauntless village people who protest, forget the religious barrier, and enquires about daring questions about religious identity. When Shovon’s Muslim friend Abdul dies, he is barred to see his corpse by his mother. Shovon inquires his mother ‘aren’t the Muslims humans, ma?’. He further asks: ‘why are all people not the same?’ ‘Why is religion bipartite? The vernacular language that the writer uses to narrate the story did not hinder me to approach the story instead I got more attached to the story as it seems pragmatic and real. The story still lives with me and gives me ripple though I consumed it twelve years ago.

The novel that immensely touched me is Gavi Bittanto. I literally could not move away from it while reading. I have just joined as a lecturer in a university and still, I find the smell of a student in me. The satire that Sofa presented in this vary book seemed so close to my experience. Nonetheless, the way Sofa revealed the malicious nature of a public university VC and his comrades is hilarious and the crafty satirical tone of the particular novel makes it a masterpiece. The novel humorously presents how university teachers skip teaching and intellectual practice and exercises political power in the university. To my utter surprise, I see, even in this 2021 Bangladeshi teachers are busy gaining political and administrative power. Teachers and vice-chancellors do not inculcate intellectual endeavour and involve themselves more in non-academic profit-making ventures.

From his young life, Ahmed Sofa was involved with politics. But he was a free thinker and never biased in his writing in every sphere of life. To everyone, he was known as a dauntless person. We find his simple but fearless nature of life reflected in each piece of his writings. He was not a follower of a trend rather he was a trendsetter. In this case, to me, Sofa’s essays are more revolutionary, radical, and very deep-seated than his novels. His arguments, sharp-razor thoughts, and his historical and political sense make Sofa a unique Bengali essayist ever born in Bangla literature. His Buddhibrittir Natun Binyas (A New Mode of Intellectualism, 1972) and Bangali Musalmaner Man (The Mind of the Bengali Muslims, 1981) took me into an ocean of deep thinking. Every single sentence seemed important to me. I must confess that these two writings and other essays of Sofa still influence me and shape my thought.

I have never read such a bold essay like Buddhibrittir Natun Binyas. Sofa here in this essay bashed the so-called Bengali intellectuals without any hesitation. As I learned that Sofa wrote this essay at the age of 26, I could not but remain in awe. It was a shock for many ill-practiced opportunistic intellectuals albeit few prominent intellectuals and would-be scholars praised the essay heavily. The most daring comment that Sofa pens down in this essay: ‘Bangladesh would have not been liberated if she listened to the intellectuals. If listen to them now, the full-scale socio-structural change will not occur in Bangladesh’. He invites intellectuals to come out from their intellectual slavery. If we do not protest, our independence in 1971 will not bring anything good. Hence, Sofa is sometimes termed as mad genius. I used to call him ‘jibon o shaitter sotto sromik’ — a true laborer of life and literature). He is a real romantic litterateur with a great vision and mission.

The long and intricate Bangali Musalmaner Man essay unfolds a new identity in me. As son of Muslim, I asked a lot of questions to my inner self while negotiating my thoughts with this exclusive writing. Sofa plainly writes that, to my understanding, Bengali Muslims are afraid of free-thinking. They have made them incapable of making their destiny. But he did not solely blame the Muslims at all instead he argues that for a long time they have gone through a conventional and manipulative historical process that has shaped their minds. Yet, Sofa invites the Bengali Muslims to listen to their hearts and not to blame others for their downfall. He further suggests them to follow the augmented domain of science, culture, and literature.

In his 1992 essay Bangladesher Uchubitto Sreni Ebong Somajbiplob Proshongo (On the Issue of Elite Class of Bangladesh and Social Struggle) ignited my young soul a lot. The sentence that stirs my thought is ‘the elites of Bangladesh pretend more foreign than the foreigners’. He clearly and logically reveals that the backwardness of the Bengali Muslims is not because that they are Muslims but because the elites keep their distance from the subalterns and subjugate them. Consequently, these oppressed people feel alienated and do not feel true belonging to anything in Bangladesh. Reading this essay, I keenly observe the sublimity and subtlety of Ahmed Sofa as a thinker and essayist. He is precise, concise, and logical still, I find, a necessary tinge of emotion and sensitivity in this thought-provoking essay.

In most of his essays, he talked about Bengali nationality and identity formation. No wonder, he wrote extensively about politics and culture that shape the identity of people. He was always concerned about identity politics and its impact on our psyche. Sofa was an accomplished literary critic nonetheless he preferred to write creative pieces. Unlike many famous writers, he was not an armchair literary figure; he was very active in meetings, road marches, and literary forums. He was up against all sorts of oppressions, be it physical or psychological.

Though I haven’t read much of his poems, I find his poetry interesting and ingenious. His long poem Basteeujar (Eviction of the Slum) portrays the exodus of the poor village people in Dhaka city and their flowery and rosy imagination of city life. The cruel picture of eviction is described in a pragmatic but heart-wrenching manner. I loved the way he uses his diction and imagery. Ekti Prabin Bater Kachhe Prarthana (Prayer to an Ancient Banyan Tree, 1977) is another poem that gripped me. Here, the banyan tree carries the history of the whole village and its identity. I loved the fragmented events and images of this poem and it takes me back to my childhood too.

It is not possible to capture the journey of Ahmed Sofa as a writer. Because of the space limit, I could not write everything that I have studied about great Sofa. But, from my limited reading of Sofa, I dare to say that he is unlike than most of the Bangladeshi writers. His boldness and courage make him different. He loved to declare his descendance from a farmer family. Every stroke of his pen is a stroke of confidence. To me, Sofa means historical sense, revolution, and creation.

I must say that reading Sofa is a must. Our old scholars have neglected him a lot. The young budding scholars and a truly sensitive and revolutionary soul who loves to see a secular and developed Bangladesh must go through his writings. Avoiding Sofa means neglecting the original history of Bangladesh and one’s own identity. So far, as a young reader of Sofa, I trust his writings the most than any other writers in Bangladesh. The spirit of Sofa is the exact spirit of 1971 and an oppression-free Bangladesh.

The writer is a poet and teaches English Literature in a private University.