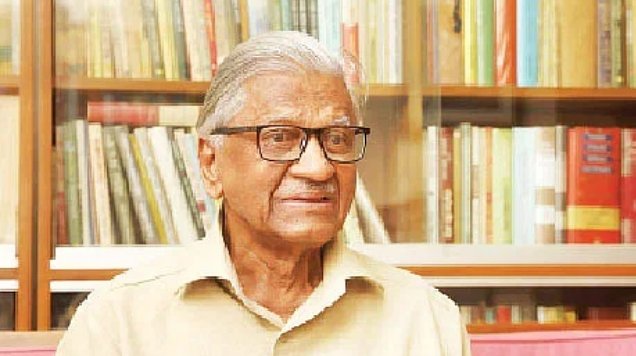

Monoj Dey: Educationist and social analyst Abul Kashem Fazlul Haque is presently professor of the Ahmed Sharif chair at Dhaka University’s Bangla department. He has written profusely on the country and politics and has a great number of books culture, the liberation war, the language movement, the middle class predicament and more. In a recent interview, he talks about the Bangla New Year, our culture, politics and such.

Question: Our culture once upon a time would resonate with a spirit of protest. Is that gradually fading?

Answer: Culture is an abstract concept. It varies from person to person, nation to nation. Culture is manifest through the overall activities of the individual and the nation. Many have the propensity to limit culture to songs, dances, plays, entertainment. In Bangladesh, the concept of a national culture emerged through various movements during Pakistan rule. Our culture found expression in our social, political and economic activities.

At a certain juncture, Hindu culture and Muslim culture stood in contradiction to each other in this region. This led to the division, separating Bengal and Punjab to form Pakistan. This was not a natural state. But those of the Pakistani ilk tried to create a Pakistani nationalism and a Pakistani national culture. On the flip side, a Bengali nationalism and national culture of East Bengal grew in East Pakistan. That was a culture of protest. The language movement, the 21-point programme of Jukta Front (United Front), Awami League’s six-point movement, Chattra Sangram Parishad’s 11-point movement, the 1969 mass uprising, the 1971 liberation war, all led to the establishment of Bengali culture and independent Bangladesh.

In independent Bangladesh, political and cultural thought and consciousness fell into disorder and danger. From the eighties, the NGOs and civil society organisations emerged. The previous culture of protest no longer flourished. The main reason behind this was that the mindset, thinking as well as the activities of the political parties became weak and perverse. The politicians and intellectuals were gripped with a strong sense of consumerism and opportunism. As a result, both politics and culture loss creativity.

Question: The cultural movement of the fifties and the sixties had also set the premise of the political movement. Culture has lost much of that independent ethos. Does culture now remain at the behest of politics?

Answer: A section of the politicians, writers, artists and intellectuals back then had been supporters of the Pakistan concept. Then again, there were those who chose to be noncommittal. Yet again, there were the writers, artists, intellectuals as well as college and university students who were strongly in favour of Bengali nationalism and Bengali culture. The students and youth of this trend, and the cultural activists, were mostly of the leftist camp. Politically speaking, Awami League and Chhatra League began to grow in popularity from 1966 with the six-point movement.

At the time, Awami League did not have any significant cultural organisation. After Bangladesh was established under the leadership of Awami League, many of the left-leaning cultural organisations and the cultural activists and leaders became supporters of Awami League. And cultural activists were also caught up in the political chaos that emerged after independent.

After the killing of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the change in political scenario in 1975, the military rulers Ziaur Rahman and Hussein Muhammad Ershad remain in power for around 15 years. In this period, cultural thought and activities came to a standstill. Many artistes, writers and intellectuals toed the military government for the sake of extra perks and benefits. Most of the intellectuals and cultural activists of the country have not been able to break away from the proclivity.

Question: There was a time when ‘jatra’ (dramatic folk theatre) was very popular at the grassroots. But all sorts of restrictions have put a dampener on this. How do you view that?

Answer: Jatra, pala gaan and such elements of popular rural culture are almost extinct now in the new reality of Bangladesh. But there is immense scope for something new emerging in Bangladesh’s present day realities, of forging ahead in progress. However, there are all sorts of efforts on the part of the rulers to control free thinking in national life.

As things stand of today, free thinkers do not have the courage to think freely. Repressive laws like the Digital Security Act have been put in place. Creating or enacting such laws, outside of the constitution, cannot be supported in any way. Space must be created for those with elevated thinking to be able to express themselves. This will benefit the politicians of all parties, cultural activists and intellectuals. Repressive policies do not bode very well.

It is essential for everyone to learn from history. But in Bangladesh, no one wants to take any lessons from history. It requires the study of Bengali culture and politics of around 1,500 years to bring about change and development to the reality in which Bangladesh stands today.

Question: All sorts of restrictions are being imported on Pahela Baisakh or Bengali New Year (Nobo Barsha) celebrations too. Are festivals losing spontaneity?

Answer: There was a time when the Bengali New Year was not celebrated in Dhaka city, the previous district towns and subdivisions. The Bengali New Year was celebrated among the Bangla-speaking rural population. With the passage of time, Nobo Barsha celebrations have changed too. It was the movement for Bengali nationalism and culture in the sixties that ushered in Nobo Barsha celebrations in city live.

In the 19th century, a Hindu mela (fair) was held on Chaitra Sangkranti (last day of the Bengali year). It had an underlying call for an end to British rule and the emergence of independent Indian and Bengali culture. In the last century, the main impetus to commemorate the 100th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore was to oppose the rule of Ayub Khan. Tagore birth centenary was celebrated in defiance of government obstruction. At the same time, aspirations grew to celebrate Nobo Barsha at an expression of Bengali nationalism and Bengali culture. It was those who had established Chhayanaut that came forward with the official observing of the Bengali New Year.

Dhaka University Teachers Association also joined in observing this day. At the time, the Bengali cultural spirit was strong among the teachers. The pro-Muslim League teachers were opposed to celebration of Nobo Barsha. But in opposing the Bengali New Year festivities, they found themselves isolated.

It was in the mid-eighties that the Mangal Shobhajatra trend began as a part of Nobo Barsha celebrations. A number of anti-Awami League religion-based organisations and individuals were opposed to this. Their stand did not gain any clout, but they still oppose this colourful rally. We should not do anything that strengthens the reactionary forces. We must observe Pahela Baishakh for our national consciousness to grow and our national culture to flourish.

Question: When festivals like Pahela Baishakh come around, social media is polarised over pro and anti groups. Where did these divisions and differences sprout from?

Answer: It is the weakness of the Bengali nationalist progressive forces that give way to the rise of the opposing force. If this division continues and if the trend of progressive thinking does not grow, the reactionaries will gather strength. In this case, the media can create scope for the progressive trend to flourish.

Question: In recent years we have seen cultural elements subservient to power. Is it the function of culture to serve the interests of those in power?

Answer: Many intellectuals are now active sycophants of the political parties. But even being with the parties, they fail to enrich the parties with elevated thinking. They don’t even try to do so. The party intellectuals are busy serving like minions of the party. This is damaging our national culture.

Given the reality in Bangladesh, other than Awami League, there is very little presence of intellectuals, writers, cultural activists and artistes in other parties. Those who cultivate their thoughts and express themselves independently, are now isolated.

Question: In fighting against Pakistan, we created Bengali nationalism as our political weapon. Do you feel the time has come to broaden our identity?

Answer: Culture has been there from the start of human history and will remain. But the concept of culture arose much later. In modern times, giving thought to nationalism, democracy, socialism, the national state and such concepts, are vital for culture. These political perceptions, in Bangladesh’s present day reality, must undergo radical change.

It has been seen that those in power never want dissenting thoughts and activities to grow. This inevitably leads to struggle. Such struggle fizzled away by the end of the seventies. In the eighties, parties like Awami League and BNP aimed their activities at toppling the government and grasping power. There is no understanding of nationalism, internationalism and globalisation within our political parties. Most of the writers, researchers and thinkers of the country also lack in depth of thought.

This problem looms large not just in Bangladesh, but the world over. Politics and intellectual pursuit in blind adherence of the western superpowers must be discarded. The political and cultural vacuum must be overcome with a realisation of our own strength and though a national struggle. It has become essential in Bangladesh to have independence in thinking and to fight for that. There is need for logical thought and scientific approach. We certainly must broaden the scope of our thinking and work.