The author speaks about his writing, about Bengali culture and politics from his days as a student activist to the present.

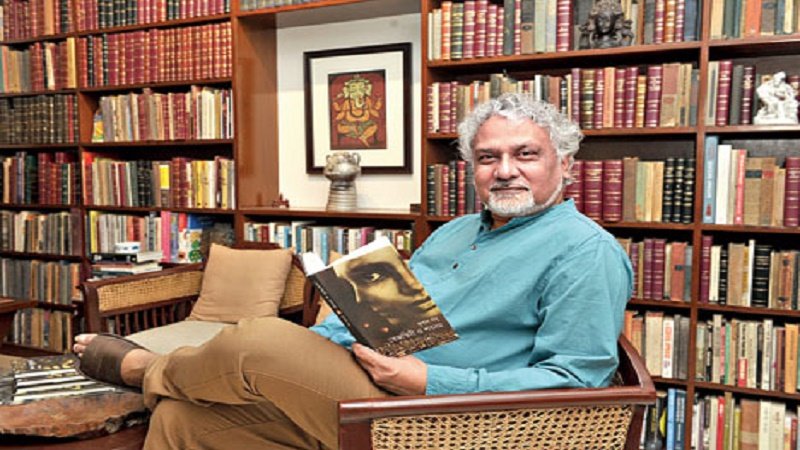

Kunal Basu is a novelist and teaches at Oxford University. In this interview with The Wire, he speaks about his writing, about Bengali culture and politics from his days as a student activist to the present.

You are among the few novelists who have written in both Bangla – your mother tongue – and in English. How did you relate to these languages and the cultures within which they are located?

I was lucky to have been born in a progressive household with an author for a mother (Chabi Basu) and a publisher father (Sunil Kumar Basu). Squarely in the Left, they were activists and litterateurs, and had both served time in jail. Poets, novelists, filmmakers and dramatists frequented our home. Feet firmly planted on Indian soil (some hadn’t even travelled beyond it), they were nevertheless world citizens whose canvas stretched from the French Nouvelle Vague to the Santhal Rebellion.

I grew up in a culture of ad-da, where Boris Pasternak was as much a bone of contention as Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay. The Naxal movement raised hackles that only the Spanish Civil War could temper. Surrounded by books, and in the company of “borderless” women and men, I believed that my tryst with life was mediated by culture, and offered an exciting passage guided only by my imagination. I didn’t have to choose between Tarashankar and Dickens, nor take sides between Bangla and that wonderful Indian language called English. Bilingualism is a clumsy word. My cultural inheritance turned me promiscuous, happy to leap from one literary stream to another.

A New York reporter had once pinned me down with a vexing question: By what license had I, an Indian, written a Victorian novel (Racists) populated solely by Europeans and Africans? Or penned a tale about the opium trade (The Opium Clerk) without any Chinese lineage in my bloodline, or for that matter a Moghul saga (The Miniaturist) despite being a non-Muslim? And how about my Bangla novels, those that aren’t set comfortably in Bengal but in Iraq and Somalia! Do you own this world? He had frowned at these cultural invasions. Linguistic facility isn’t enough to inhabit multiple worlds; I had tried to explain to him. It has to do, primarily, with a sensibility that is cultural in scope, political in intent and humanistic in aspiration – a sensibility that I’d imbibed early as a precocious child from my parents and their friends.

Many of your novels are rooted in Kolkata, the city you grew up and studied in. Also the city where you became a Left political activist. How has Kolkata featured in your work?

I had resisted writing about Kolkata for many years, principally to avoid the trap of nostalgia, a sort of petty yearning for the past that rarely yields anything weightier than bittersweet (and ultimately banal) memories. I didn’t want Kolkata to smell of dead fish recovered from a freezer, but the fresh blood of a fish market. My Kolkata novels – Kalkatta and Sarojini’s Mother – are novels of exploration. I wanted, consciously, to debunk the stock-in-trade of Indo-English novels that present a lucidly graspable city easy to identify with or recognise from afar. I wanted my Kolkata to fleet like a wolf from light to darkness. I know this city like the back of my palm, and yet wished to make my way through it blindfolded, guided purely by the strangeness of sensations, the unspeakable crudities as well as the ethereal moments it has to offer.

My Kolkata novels, therefore, are stories of surprise, horror, orgasm and pain, and the only way I could impart such was to leave my moorings and journey through the city’s troubled waters. Thus, Kalkatta plunges into the lives of male prostitutes and undocumented immigrants; Sarojini assembles a cast of racecourse bookies, illegal fight clubs, musical bands – travels from slums to the Bengal Club, the planetarium to the prison. Like all diverse metropolises, Kolkata doesn’t have one heart but many, with stories waiting to burst out of them.

God has abandoned our world – Sartre had written. Perhaps Kolkata is what is left behind, to help us repent.

What about Kolkata and Bengali society? What have been the most significant influences impacting the people?

It’s hard to avoid clichés when speaking about change. Undeniably, a clear chasm separates Kolkata of the 70s and the thereafter, but it is pointless to debate its “root cause.” Far too many wounds have scarred the city and although the political symptoms are clear, a deeper shifting of tectonic plates has played a crucial hand in the makeover.

A cultural hothouse in the 60s and 70s, Kolkata and Bengal boasted avant-garde theatre, global cinema, modernist poetry, an explosion of little magazines, the world’s largest book bazaar (College Street), the biggest literary festival (Banga Sahitya Sammelan), the busiest film society movement, a vibrant contemporary Indian art (The Bengal School) a teashop and a coffee house culture not inferior to European literary salons. Culture dovetailed into politics; mass movements spurred iconic plays and music; and the Left was synonymous with culture not power. There were blind spots as well – a kind of misplaced Bengali arrogance, along with a tendency to gloss over caste and gender fault lines, plus messy squabbles between the “soft” and the “hard” Left. But these were failures of the mind, not of the heart. Critically, culture mattered. The cultured person was valued beyond his/her net worth. Revered as they were, individual stalwarts weren’t elevated to celebrity status. A kind of naivety prevailed, that saw culture as a collective force for social justice. Despite personal rivalries, the flower of innocence bloomed.

Liberalisation and the Left Front changed all that. The first championed individual ambition over collective salvation, the second turned culture into a handmaiden of political power. It wasn’t relevant to fight the system any more; it offered career options to creative individuals and co-opted a whole lot of them through state grants. Bereft of a heart, culture became simply hands and feet, and lost its edge. Now after three decades of the reign of the twin terminators, it isn’t just blunt but softer than putty.

Today’s Bangla fiction is a study of the pathology of the privileged. The poor have been photoshopped out of the plot. Now NRIs triumph over the BPL, and pasta reigns over rice. It stands in direct contrast to the empathy that was so much resonant in the works of our stalwarts (Saratchandra, Bibhutibhushan, Tarashankar, Manik…). This self-indulgent navel gazing has produced a literature of emptiness, without an emotional core or an intellectual quest. Readership is seriously down, with independent bookshops closing down, and College Street has turned into a bazar for exam study guides. A successful author can expect no more than just 800 copies of annual sale of their book, and a single review if lucky. The feudalism of Bengali publishers has led to a self-exile from e-channels, and a rift has opened up between Bangla and English heightening a sense of victimhood among local writers.

In such a cultural wasteland, the leading Bengali TV channel has proscribed all programming on books citing TRP risk. In fact, only the much-maligned Doordarshan has the guts to buck the trend. Bengali cinema has entered a phase of faux-Bengaliness, celebrating middle class minutia and remix of detective stories, while Bangla bands parrot lovesick lyrics garnished with clever wordplay. An aura of self-glorification is pervasive. Criticise at your own risk or be banned from Bengal’s hallowed culture club. Things are a bit better in the districts, one’s told, but the muffasil wave hasn’t turned into a tsunami yet.

Bengal and Kolkata are now a part of the homogeneous heartland. Cultural depravity is bound to take its toll on our psyche, and in Kolkata/Bengal it has led to rampant political vandalism and violence … the barbarians are now truly at the gate.

Tell me about your latest book Sarojini’s Mother which is about belonging. The novel comes at a time the country is engaged in a bitter contest about citizenship. What does the idea of belonging mean to you?

Sarojini – Saz – Campbell has come to India to search for her biological mother … so the story goes. Although it isn’t uncommon for adoptees to come looking for their kin, the strangeness of Sarojini’s tale derives from the fact that once in India, she finds two mothers instead of one. Both women appear to have prima facie evidence in their favour, which leads to much confusion. Sarojini’s quest enters uncharted philosophical waters when she must decide if biology would settle the issue of motherhood or is it psychology – the quality of affection she feels for either of these two women. Would her belongingness depend upon real feelings or the cold facts of science?

unintentional, Sarojini’s dilemma is strangely resonant of the current debate over citizenship. Is biological proof mandatory and enough to establish one belongs to this nation? How about those – the super rich and the NRI – who’ve closeted themselves apart from the lives of their fellow citizens? In their “biologically valid” selfishness, do they qualify as true Indians? For the multitudes that will face challenges in biological terms, isn’t their love and sacrifice enough? After all, it is this power of mutual affection (the hackneyed but true ‘Unity in Diversity’) that has made India what it is today not the sham of a forensic test.

What will Sarojini enshrine in her biography – biology or psychology? Read on…

Bengal is in political flux. The Hindu Right has more than a toehold in a state, once considered a Left bastion. Your thoughts about the emergence of the electoral Hindu Right here

Fascism finds its home in an empty vessel. And a Bengal, bereft of dreams, has been running on empty for a very long time. The biggest crime of the Left was to turn a popular movement into an administrative machine. In trying to beat the “ruling class” in their own game, it became the ruling class. Those who followed simply copied the formula, elevated vandalism to the norm. If you don’t believe in a greater good, you will be moved by pettiness, by blame-gaming; prejudice will become an attractive calling card.

The Hindu Right has been handed an opportunity, and even if they can be beaten back in electoral terms by some turn of events, their footprint is likely to grow. Sadly, many Bengalis have crossed the line of no return. The Partition has been resurrected for all the wrong reasons. Yet, I do believe that the resistance to all this will eventually succeed – Kolkata and Bengal have always proved the doubters wrong. From the Santhal Rebellion to Naxalbari, we have surprised everyone including ourselves. A Bengal Renaissance may just be around the corner. Interview taken by Monobina Gupta