।। Raina Sabanta ।।

As Queen Elizabeth II, the longest reigning British monarch – she was the queen for 70 years and 214 days – passed away last week, a clear division of opinion regarding how it should be perceived manifested. While there was a relentless outpouring of grief, those living in countries adversely affected by the oppressive institution she represented noted the fallacy in how her legacy was being reported. Nevertheless, with so many conversations pertaining to her as an individual, an opaque veil was inevitably placed over the British rule of Bengal, which opened a Pandora’s Box of ills that causes us unparalleled suffering to this day.

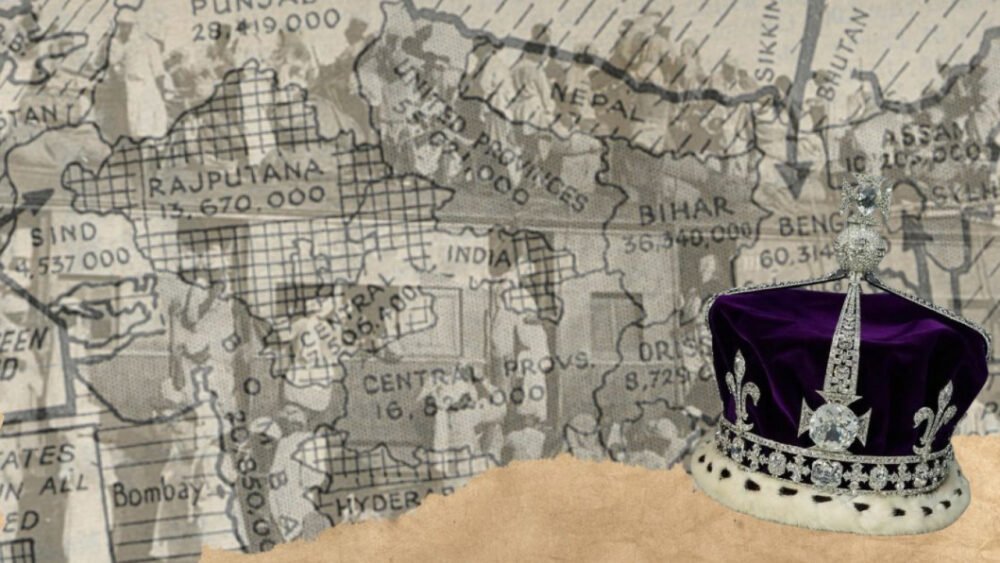

Out of all the 15 UK prime ministers who served under Queen Elizabeth II, Winston Churchill was indubitably her favourite. He was the architect of the catastrophic 1943 Bengal famine, the only one in modern Indian history not caused by a drought. An estimated 2.1 to 3.8 million Bangalees, out of a population of 60.3 million, perished owing to Churchill’s wartime cabinet policies, which amplified the severity of the famine. Rice, a staple for Bengal, was being exported to other parts of the British Empire, despite the cabinet being cautioned that it would be detrimental to the region. Churchill opted to blame the famine on the Bangalees “breeding like rabbits,” along with making some unsavoury remarks about Mohandas Gandhi, sarcastically questioning as to why Gandhi was still alive if the famine was so severe. The adversity that resulted due to his apathetic response can be explained by the Thrifty Gene Hypothesis, which suggests that the carriers of “thrifty genes” survive because they deposit fat between famines. It implies that the people of the subcontinent are more prone to diabetes, heart issues and obesity. Hence, our inclination towards suffering from such diseases can directly be traced back to oppressive British colonial policies.

It is famously said that all the problems in the world started with the British drawing a line on the map. Their much-adored game of “divide and rule” began with deliberately causing religious rifts within the population of Bengal. Matters came to a head when, after 200 years, the British left its last parting gift to independent India in 1947: Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan. It was done with heartlessness, outdated maps, little to no knowledge of the lands, and, most importantly, behind closed doors without the consultation of local political figureheads. At least one million people lost their lives owing to the British expediting their withdrawal, which in turn created a power vacuum. Punjab witnessed most of the violence, where 100,000 women were kidnapped and their lives brutalised. The horribly drawn map, a courtesy of the British rulers, caused lingering divisions and border disputes, which are perhaps etched too deeply to ever be resolved. Although Bangladesh gained its independence in 1971 from Pakistan, Kashmir is still a disputed region between India and Pakistan for 75 years. The Partition of India is one of the darkest moments in history, where negligence of the British left a permanent gaping hole in the heart of the subcontinent.

Many have argued that Queen Elizabeth II ensured a smooth transition of the Empire to a Commonwealth, hence absolving her of any accountability of her predecessors’ actions, while others believe that she represented a historically oppressive empire too perfectly, with all the requisite traits. Although the latter argument carries more weight, individualising such a crime is a terrible idea. As much as it is imperative to consider Queen Elizabeth’s detrimental actions towards her inherited “subjects,” it is even more pressing to view the institution she represented as problematic in its very essence. The Queen may be no more, but the institution remains as sturdy as ever. We should not use death to reconcile the actions of the living, or use respect for tradition as an excuse to continue exalting outdated establishments – especially when they boast unforgivable atrocities committed against minorities with blatant disregard and complete impunity.

It was once said the sun never sets on the British Empire, which is often viewed and promoted as a splendid achievement. But we must also remember that history is always penned by the victorious, and it is done irrespective of whether or not they are bloodthirsty oppressors. People of colour, the prime victims of British colonisation, should not be forced to identify with their oppressors – worse yet, empathise with them. It is time for the West, who are too blinded by their white privilege, and South Asians, who are suffering from something akin to Stockholm syndrome, to stop lauding colonisation and romanticising it. It is long overdue for those defeated and oppressed to tell their side of the story. The said story starts with identifying the British Monarchy as an institution that is a dazzling and painful reminder of Bengal’s (Bangladesh and West Bengal) traumatic past, a robust foundation to dismantle and not something to glorify and venerate.

Raina Sabanta is an aspiring barrister.